US-Ukraine deal highlights Ukraine’s wealth of critical minerals, but extracting them isn’t so simple

Ukraine’s mineral wealth has been a key factor in its negotiations with the U.S. as the two countries work out details for a ceasefire agreement in Ukraine’s war with Russia.

After a rocky start to those negotiations, officials from the U.S. and Ukraine announced an agreement on March 11, 2025. The U.S. agreed to resume support and intelligence sharing with Ukraine, and both agreed to work toward “a comprehensive agreement for developing Ukraine’s critical mineral resources to expand Ukraine’s economy, offset the cost of American assistance and guarantee Ukraine’s long-term prosperity and security.” Getting Russia to agree to a ceasefire would be the next step.

There’s no doubt that Ukraine has an abundance of critical minerals, or that these resources will be essential to its postwar reconstruction. But what exactly do those resources include, and how abundant and accessible are they?

The war has severely limited access to data about Ukraine’s natural resources. However, as a geoscientist with experience in resource evaluation, I have been reading technical reports, many of them behind paywalls, to understand what’s at stake. Here’s what we know.

Ukraine’s minerals fuel industries and militaries

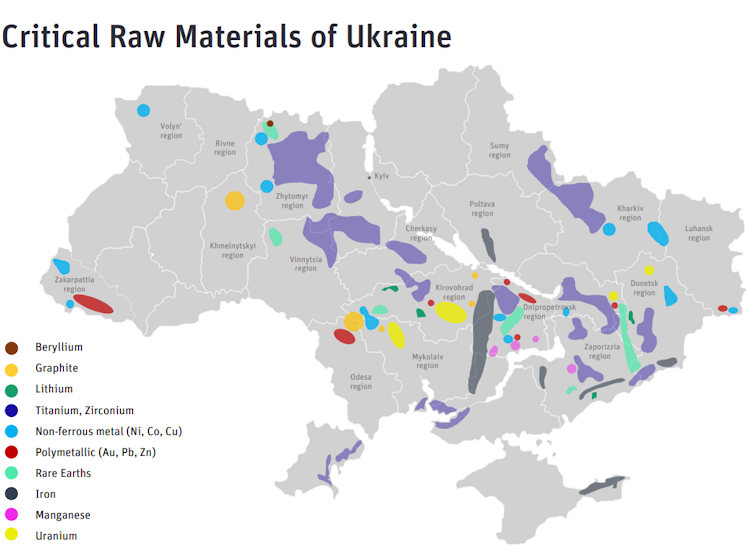

Ukraine’s mineral resources are concentrated in two geologic provinces. The larger of these, known as the Ukrainian Shield, is a wide belt running through the center of the country, from the northwest to the southeast. It consists of very old, metamorphic and granitic rocks.

A multibillion-year history of fault movement and volcanic activity created a diversity of minerals concentrated in local sites and across some larger regions.

A second province, close to Ukraine’s border with Russia in the east, includes a rift basin known as the Dnipro-Donets Depression. It is filled with sedimentary rocks containing coal, oil and natural gas.

Before Ukraine’s independence in 1991, both areas supplied the Soviet Union with materials for its industrialization and military. A massive industrial area centered on steelmaking grew in the southeast, where iron, manganese and coal are especially plentiful.

By the 2000s, Ukraine was a significant producer and exporter of these and other minerals. It also mines uranium, used for nuclear power.

In addition, Soviet and Ukrainian geoscientists identified deposits of lithium and rare earth metals that remain undeveloped.

However, technical reports suggest that assessments of these and some other critical minerals are based on outdated geologic data, that a significant number of mines are inactive due to the war, and that many employ older, inefficient technology.

That suggests critical mineral production could be increased by peacetime foreign investment, and that these minerals could provide even greater value than they do today to whomever controls them.

Why the US is so interested

Critical minerals are defined as resources that are essential to economic or national security and subject to supply risks. They include minerals used in military equipment, computers, batteries and many other products.

A list of 50 critical minerals, created by the U.S. Geological Survey, shows that more than a dozen relied upon by the U.S. are abundant in Ukraine.

A majority of those are in the Ukrainian Shield, and roughly 20% of Ukraine’s total possible reserves are in areas currently occupied by Russia’s military forces.

Critical minerals Ukraine currently mines

Three critical minerals especially abundant in Ukraine are manganese, titanium and graphite. Between 80% and 100% of U.S. demand for each of these currently comes from foreign imports..

Manganese is an essential element in steelmaking and batteries. Ukraine is estimated to have the largest total reserves in the world at 2.4 billion tons. However, the deposits are of fairly low grade – only about 11% to 35% of the rock mined is manganese. So it tends to require a lot of material and expensive processing, adding to the total cost.

This is also true for graphite, used in battery electrodes and a variety of industrial applications. Graphite occurs in ore bodies located in the south-central and northwestern portion of the Ukrainian Shield. At least six deposits have been identified there, with an estimated total of 343 million tons of ore– 18.6 million tons of actual graphite. It’s the largest source in Europe and the fifth largest globally.

Titanium, a key metal for aerospace, ship and missile technology, is present in as many as 28 locations in Ukraine, both in hard rock and sand or gravel deposits. The size of the total reserve is confidential, but estimates are commonly in the hundreds of millions of tons.

A number of other critical minerals that are used in semiconductor and battery technologies are less plentiful in Ukraine but also valuable. Zinc occurs in deposits with other metals such as lead, gold, silver and copper. Gallium and germanium are byproducts of other ores – zinc for gallium, lignite coal for germanium. Nickel and cobalt can be found in ultramafic rock, with nickel more abundant.

No figures for Ukraine’s reserves of these elements were available in early 2025, with the exception of zinc, whose reserves have been estimated at around 6.1 million tons, putting Ukraine among the top 10 nations for zinc.

Critical minerals that aren’t being mined – yet

Geologists have identified potentially significant volumes in Ukraine of three other types of critical minerals important for energy, military and other uses: lithium, rare earth metals and scandium.

None of these had been mined there as of early 2025, though a lithium deposit had been licensed for commercial extraction.

The largest potential lithium reserves exist at three sites in the south-central and southeastern Ukrainian Shield, where the grade of ore is considered moderate to good. How much lithium these reserves hold remains confidential, but technical reports suggest it’s on the order of 160 million tons of ore and 1.6 million to 3 million tons of lithium oxide. If most of this could be recovered in a profitable way, it would place Ukraine among the top five nations for lithium.

Smaller volumes of tantalum and niobium, also used in steel alloys and technology, have also been identified in these reserves. Most of Ukraine’s lithium occurs as petalite, which, unlike the other main lithium mineral, spodumene, requires more expensive processing.

Rare earth elements in Ukraine are known to exist in several sites of volcanic origin and in association with uranium in the south-central portion of the Ukrainian Shield. These haven’t been developed, though sampling has indicated commercial potential in some sites, while other sites appear less viable.

Rare earth elements in high demand for superior magnets and electronics – neodymium, praseodymium, terbium and dysprosium – are all present in varying amounts in these areas. Other critical minerals are associated with these deposits, especially zirconium, tantalum and niobium, in undetermined but potentially significant amounts.

Finally, scandium, used in aluminum alloys for aerospace components, has been identified as a byproduct of processing titanium ores. Ukraine’s scandium does not appear to have been studied in enough detail to evaluate its commercial potential. However, world production, about 30 to 40 tons per year, is forecast to grow rapidly.

Ukraine’s mineral future

It’s clear that Ukraine is endowed with valuable resources. However, extracting them will require roads and railways for access, infrastructure such as electricity and mining and processing technology, investment, technical expertise, environmental considerations and, above all, cessation of military conflict.

Those are the true determinants of Ukraine’s mining future.

This article, originally published March 11, 2025, has been updated with the announced agreement.

Scott L. Montgomery does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

from The Conversation – Articles (US) https://ift.tt/BNpw51r

No comments: